Nuove avventure sotterranee

Nuove avventure sotterranee

A Brief History of Photography in Six Images

An Essay by Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Una breve storia della fotografia in sei immagini

Un testo di Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

The Pure Image

Domingo Milella and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

La pura immagine

Una conversazione tra Domingo Milella e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Faithful Accuracy

Luca Nostri and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Una fedele esattezza

Una conversazione tra Luca Nostri e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Nautilus

Giulia Parlato and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Nautilus

Una conversazione tra Giulia Parlato e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Brisbane Songlines

Rachele Maistrello and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Brisbane Songlines

Una conversazione tra Rachele Maistrello e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Canadiana

Stefano Graziani and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Canadiana

Una conversazione tra Stefano Graziani e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Di roccia, fuochi e avventure sotterranee

Di roccia, fuochi e avventure sotterranee

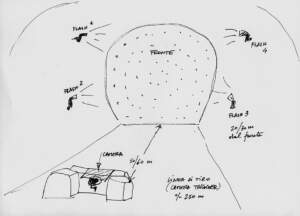

Building an Image

An Essay by Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Costruire un’immagine

Un testo di Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Conceptual Traces of Geology

Fabio Barile and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Le trame concettuali della geologia

Una conversazione tra Fabio Barile e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Many Fires Burn Below The Surface

Andrea Botto and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Molti fuochi ardono sotto il suolo

Una conversazione tra Andrea Botto e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Detour In Hanoi

Francesco Neri and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Detour In Hanoi

Una conversazione tra Francesco Neri e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Hippodamus

Marina Caneve and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Ippodamo

Una conversazione tra Marina Caneve e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Martian Chronicles

Alessandro Imbriaco and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Cronache marziane

Una conversazione tra Alessandro Imbriaco e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

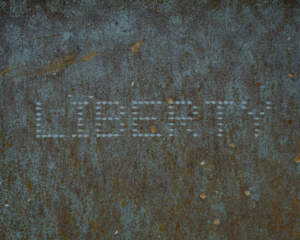

Middle-Earth. A journey Inside Elica

Middle-Earth. A journey Inside Elica

A Conversation

Fabio Barile, Francesco Neri and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Una conversazione

Fabio Barile, Francesco Neri e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

An Essay by Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Louis Daguerre did not invent photography. In 1839 there were many similar processes for recording and fixing photographic images, and there are many pioneers in the history of photography. Yet, our natural mechanism of understanding by simplification leads us to record only a few names and dates, a few well-aligned islands in the vast ocean of complexity. And the same is true for all the developments of the photographic language. We manage to associate certain names and dates with each season of the photographic medium and forget that culture and ideas evolve more as a constant flow of intuitions and imitations, things that become thinkable because they are suddenly technically possible, and incremental contributions from who knows how many authors buried in the folds of time.

However, if we happened to look at even the smallest part of what has remained hidden, we could find an unprecedented body of images in the photographic archive of a company like Ghella, which traces all phases of the history of photography, from the second half of the 19th century to the present day. We would come across new names and dates and glimpse unexpected geographies. The succession of canons of representation over time would seem more the result of the widespread sentiment of the different eras than the invention of individual creative geniuses. And if we were to attempt to superimpose Ghella’s visual memory on the chronology of the transformations of the photographic language, we could confuse the two narratives until making them coincide.

What follows is a brief history of photography in six images. It is the story of a company, a family and one of the greatest inventions of the 19th century.

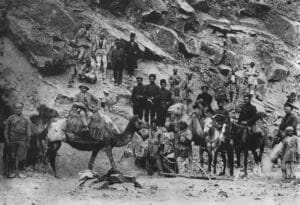

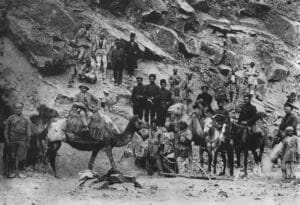

1 — The Orientalists (or Francis Frith)

In 1839, the Commission des Monuments Historiques in France realized that the fledgling medium of photography could be put at the service of archaeological exploration. Indeed, travel studies, picturesque landscapes, ancient monuments and archaeological documents formed the basis for the first photo books. The imagery captured by photographers such as Maxime Du Camp, Francis Frith and Antonio Beato were exhibited in Europe as panoramas of a glorious journey from the heroic memories of antiquity to the astonishing accomplishments of technological progress. Orientalist painting lent photography its canons of visual representation, techniques for approaching the image and a wide array of subjects that had become emblematic of a new Grand Tour.

2 — The New Objectivity (or August Sander)

By the second half of the 19th century, it was already evident that photography could be used to gather knowledge and that photographic images were capable of accurately rendering reality, silencing the individual and momentary emotions that underpin every single glance. The idea of a great archive of the world suddenly seemed possible, for the mechanical eye and memory of the camera promised the absolute impartiality of the archivist. In Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts, August Sander tasks the objective eye of the lens with capturing the numerous types of humanity that characterized early 20th-century German society, fusing the notion of classification and sociological knowledge in the photographic image.

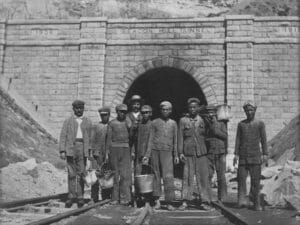

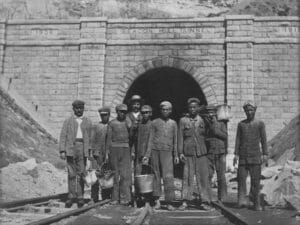

3 — The Modern Era (or Lewis Hine)

With the advent of the 20th century, photography was put at the service of both industrial advertising and political propaganda. The age of the machine and the heroic worker of the 1930s, whose heyday could be seen in the Soviet Union in the work of Alexander Rodčenko and in Germany in that of Albert Renger-Patzsch, reached its culmination in the United States with the book that the Macmillan Company commissioned from Lewis Hine. In Men at Work: Photographic Studies of Modern Men and Machines, Hine photographed workers toiling on construction sites and railways, and in machine shops, blast furnaces and mines, documenting their interactions with machines in the modern world and celebrating their contribution to shaping progress.

4 — The Documentary Style (or Walker Evans)

From the mid-1930s, the ambiguity of the photographic document became the basis for a rethinking of photography. John Szarkowski offers a good description of it: “It was at this moment that sophisticated photographers discovered the poetic uses of bare-faced facts, presented with such fastidious reserve that the quality of the picture seemed identical to that of the subject. The new style came to be called documentary. This approach to photography was most clearly defined in the work of Walker Evans.” The neutrality and detachment of these photographers from the subject results in a portrayal capable of informing as well as reflecting on our perception of the world, accepting its underlying paradox. Suddenly documentary style and art – two hitherto irreconcilable extremes – ceased to rule each other out.

5 — New Topographics (or Lewis Baltz)

In the 1970s, the vast area of work of photographers who focused on documenting the changes taking place in the contemporary landscape, in the historical shift from industrial to post-industrial economy, took shape. In 1975, the exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape acknowledged that the formal and neutral detachment of the photographic document had the potential to revive our interpretative abilities, embraced the “documentary style” proposed by Walker Evans, and introduced a radical change from the traditional depiction of the landscape. Pictures of sublime natural panoramas gave way to unromantic visions of desolate industrial landscapes, suburban sprawl and everyday scenes.

6 — The Vernacular Style (or Stephen Shore)

The recognition of colour photography as an art form is the result of a process of aesthetic emancipation that commenced in the 1970s. The first artists to take colour beyond the domain of functional or vernacular photography – terms used to distinguish artistic photographs from commercial, scientific or amateur ones – included names such as William Eggleston and Stephen Shore. Their interest in ordinary architecture and mundane aspects of American popular culture, coupled with a vaguely diaristic approach and non-hierarchical framing of the image, produced an aesthetic of colour photography based on qualities that appear to contradict their claim to be art. The vernacular, adopted as both subject and style, became the means to deconstruct and renew the rules of the photographic language.

During the same period, continual technological improvements, combined with the growing use of electronics and automation, made cameras increasingly easy to use and turned the photographer’s trade into a job accessible to everyone. The task of documenting the progress of the construction sites of companies such as Ghella started to be entrusted to anyone on site with a camera. Engineers, architects and technicians of various kinds helped to shape a new imagery of the construction site with their involuntary aesthetics. Vernacular photography – the kind without any artistic intentions, depicting ordinary events and everyday family life – entered the vocabulary of industrial photography.

Nuove avventure sotterranee (“New Underground Adventures”) brings together a selection of 32 colour images documenting infrastructures built by Ghella between the late 1960s and early 2000s (before digital photography became accessible to the general public) with the new photographic campaigns commissioned by the company between 2022 and 2023 at construction sites in Auckland, Brisbane, Buenos Aires, Naples and Vancouver.

The difference between the two groups of photographs lies in the language. The archive photographs collected in this book, shot on 35 mm film, grainy and often illuminated by artificial lights, depict the everyday life of the construction site and appear as a haphazard collection of ordinary moments, an accumulation of fragments that reflect the experience of seeing in an unfiltered manner. By contrast, the new photographic campaigns by Stefano Graziani, Rachele Maistrello, Domingo Milella, Luca Nostri and Giulia Parlato explore the same world but with greater awareness. On the one hand, due to the large amount of information condensed in each frame, on the other, thanks to each photographer’s ability to project the atmosphere of the construction site onto their personal work in an extraordinarily consistent way.

Observing the construction sites is just the starting point for a series of reflections on the clichés of depiction and the ambiguity of the photographic document, on excavation as a dreamlike interpretation of the intangible aspects of the landscape, on the symbolism of the cave and abstraction, and on the flow of the river and the depths of the sea as renderings of the city’s nature, shape and emergencies. All these factors turn their work into a contemplation of the meaning of images, reminding us once again that a photograph can be a document and an act of the imagination, a record and a possibility, all at the same time.

Un testo di Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Louis Daguerre non ha inventato la fotografia. Nel 1839 esistevano molti processi simili per registrare e fissare le immagini fotografiche e nella storia della fotografia esistono diversi pionieri. Eppure, il meccanismo di semplificazione che ci è connaturato ci porta a registrare solo alcuni nomi e alcune date, poche isole ben allineate nel vasto oceano della complessità. E lo stesso vale per le evoluzioni del linguaggio fotografico: riusciamo ad associare alcuni nomi e alcune date ad ogni stagione del mezzo fotografico e dimentichiamo che la cultura e le idee evolvono più come un flusso continuo di intuizioni e imitazioni, di cose che diventano pensabili perché improvvisamente sono tecnicamente possibili e di contributi incrementali di chissà quanti autori sommersi nelle pieghe del tempo.

Ma se ci capitasse di osservare anche una minima parte di ciò che è rimasto nascosto, potremmo scoprire nell’archivio fotografico di un’azienda come Ghella un inedito corpus di immagini che attraversa tutte le fasi della storia della fotografia, dalla seconda metà del XIX secolo fino ai nostri giorni. Incontreremmo nuovi nomi e nuove date e scorgeremmo inaspettate geografie. I canoni di rappresentazione che si sono succeduti nel tempo ci sembrerebbero più il risultato del sentire diffuso delle diverse epoche che l’invenzione di singoli geni creativi. E se tentassimo di sovrapporre la memoria visiva di Ghella alla cronologia delle trasformazioni del linguaggio fotografico, potremmo confondere le due narrazioni fino a farle coincidere.

Quella che segue è una breve storia della fotografia in sei immagini. È la storia di un’azienda, di una famiglia e di una tra le più grandi invenzioni del XIX secolo.

1 — Gli Orientalisti (o Francis Frith)

Nel 1839, in Francia, la Commission des Monuments Historiques riconosce che la neonata fotografia può essere messa al servizio dell’esplorazione archeologica. Studi di viaggio, paesaggi pittoreschi, monumenti antichi e documenti archeologici costituiscono la base dei primi libri fotografici. L’immaginario catturato da fotografi come Maxime Du Camp, Francis Frith e Antonio Beato viene mostrato in Europa come il panorama di un glorioso viaggio dalle memorie eroiche dell’antichità fino ai successi strabilianti del progresso tecnologico. La fotografia acquisisce dalla pittura orientalista codici di rappresentazione, tecniche di approccio all’immagine e un gran numero di soggetti divenuti emblematici di un nuovo Grand Tour.

2 — La Nuova Oggettività (o August Sander)

Già dalla seconda metà del XIX secolo, si comprende che la fotografia può svolgere un compito di natura conoscitiva e che le immagini fotografiche sono in grado di restituire la realtà nella sua esattezza, tacitando le emozioni individuali e momentanee che sorreggono ogni singolo sguardo. L’idea di un grande archivio del mondo sembra improvvisamente possibile perché l’occhio e la memoria meccanica della macchina fotografica promettono l’assoluta imparzialità dell’archivista. August Sander, in Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts, affida allo sguardo oggettivo dell’obiettivo il compito di rilevare i molteplici tipi di umanità che caratterizzano la società tedesca di inizio Novecento, sintetizzando nell’immagine fotografica l’idea della classificazione e della conoscenza sociologica.

3 — L’epoca moderna (o Lewis Hine)

Con l’avvento del XX secolo, la fotografia viene messa al servizio tanto della pubblicità industriale quanto della propaganda politica. L’età della macchina e del lavoratore eroico degli anni Trenta, che vede la sua apoteosi in Unione Sovietica nel lavoro di Alexander Rodčenko e in Germania in quello di Albert Renger-Patzsch, culmina negli Stati Uniti con il libro commissionato a Lewis Hine dalla Macmillan Company. In Men at Work: Photographic Studies of Modern Men and Machines, Hine fotografa operai al lavoro in officine meccaniche, cantieri di costruzioni, altiforni, ferrovie e miniere, documentando l’interazione del lavoratore con le macchine nel mondo moderno e celebrando il loro contributo alla costruzione del progresso.

4 — Lo stile documentario (o Walker Evans)

Dalla metà degli anni Trenta, l’ambiguità del documento fotografico viene posta come base per un ripensamento della fotografia. John Szarkowski ne dà una buona descrizione: “In quel periodo alcuni fotografi raffinati scoprirono l’uso poetico dei fatti guardati in modo diretto, presentati con un distacco tale che la qualità dell’immagine sembrava identica a quella del soggetto fotografato. Questo nuovo stile si fece chiamare documentario, e si è definito nel modo più chiaro nell’opera di Walker Evans”. La neutralità e il distacco di questi autori dal soggetto produce una rappresentazione capace di informare, come pure di riflettere sulla nostra percezione del mondo, accettandone il paradosso di fondo. A un tratto stile documentario e arte, due poli fino ad allora inconciliabili, smettono di escludersi.

5 — Nuovi topografici (o Lewis Baltz)

Negli anni Settanta, prende forma la vasta area di lavoro dei fotografi che si dedicano allo studio dei mutamenti in corso nel paesaggio contemporaneo, nel passaggio storico dall’economia industriale a quella post-industriale. Nel 1975, la mostra New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape riconosce al distacco formale e neutrale del documento fotografico la potenzialità di rigenerare le nostre capacità di lettura, fa suo lo stile documentario proposto da Walker Evans e introduce un cambiamento radicale rispetto alla tradizionale rappresentazione del paesaggio. Le immagini di sublimi panorami naturali lasciano il posto a visioni non romantiche di desolati paesaggi industriali, espansioni suburbane e scene quotidiane.

6 — Lo stile vernacolare (o Stephen Shore)

Il riconoscimento della fotografia a colori come forma d’arte è il risultato di un processo di emancipazione estetica iniziato negli anni Settanta. I primi artisti a portare il colore oltre il dominio della fotografia funzionale o vernacolare – termini utilizzati per distinguere le fotografie artistiche da quelle commerciali, scientifiche o amatoriali – sono autori come William Eggleston e Stephen Shore. Il loro interesse per l’architettura ordinaria e per gli aspetti banali della cultura popolare americana, insieme all’approccio vagamente diaristico e all’inquadratura non gerarchica dell’immagine, produce un’estetica della fotografia a colori a partire da qualità che sembrano contraddire la loro pretesa di essere arte. Il vernacolare, assunto sia come soggetto sia come stile, diventa il mezzo per decostruire e rinnovare le regole del linguaggio fotografico.

In quegli stessi anni, il continuo miglioramento della tecnologia, così come il sempre maggiore ricorso all’elettronica e all’automazione, rendono le fotocamere sempre più semplici da usare e trasformano il mestiere del fotografo in un lavoro alla portata di tutti. La documentazione degli stati di avanzamento dei cantieri di un’azienda come Ghella inizia a essere affidata a chiunque si trovi sul posto con una macchina fotografica. Ingegneri, architetti e tecnici di vario genere contribuiscono con la loro estetica involontaria a dar forma a un nuovo immaginario del cantiere. La fotografia vernacolare, quella priva di intenzione artistica, quella degli avvenimenti ordinari e della quotidianità in famiglia, entra nel vocabolario della fotografia industriale.

Nuove avventure sotterranee mette in dialogo una selezione di trentadue immagini a colori che documentano infrastrutture realizzate da Ghella tra la fine degli anni Sessanta e l’inizio dei Duemila (prima che la fotografia digitale divenisse accessibile al grande pubblico) con le nuove campagne fotografiche commissionate dall’azienda tra il 2022 e il 2023 nei cantieri di Auckland, Brisbane, Buenos Aires, Napoli e Vancouver.

La differenza tra i due corpus fotografici sta nel linguaggio. Le fotografie d’archivio raccolte in questo libro, scattate in 35 mm, granulose e spesso illuminate da luci artificiali, rappresentano la quotidianità del cantiere e si presentano come una raccolta disordinata di momenti qualsiasi, un accumulo di frammenti che riflettono in modo non filtrato l’esperienza del vedere. Al contrario, le nuove campagne fotografiche, realizzate da Stefano Graziani, Rachele Maistrello, Domingo Milella, Luca Nostri e Giulia Parlato, esplorano lo stesso mondo, ma con una consapevolezza aumentata. Da un lato, per la grande quantità di informazioni condensate in ogni fotogramma; dall’altro, per la capacità di ogni autore di proiettare l’atmosfera del cantiere nelle rispettive ricerche personali in modo straordinariamente organico.

L’osservazione dei cantieri è solo il punto di partenza per una serie di riflessioni sui cliché della rappresentazione e sull’ambiguità del documento fotografico, sullo scavo come lettura onirica degli aspetti intangibili del paesaggio, sul simbolismo della caverna e sull’astrazione, sullo scorrere del fiume e sulle profondità del mare come restituzioni del carattere, della forma e delle emergenze della città. Tutti questi fattori trasformano il loro lavoro in una meditazione sul senso delle immagini e ci ricordano, ancora una volta, che una fotografia può essere un documento e un atto dell’immaginazione, una registrazione e una possibilità, tutto nello stesso tempo.

Domingo Milella and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

In the necropolises of Tuscia, in the rock-hewn churches in Cappadocia, and, many years earlier, in Lascaux, I saw that there is a direct link between the cave and the spirit, as strong as that which connects the sky and the mind.1

AD: The few lines that we’ve chosen as an introduction to our conversation trace a path that sums up your line of artistic enquiry over the past twenty years with that simplicity and clarity that fill us with awe whenever we encounter our own thoughts in the words of others.

DM: I’ve been working with caves and prehistoric art for eight years. So I already had this relationship with caves and the primitive, the imagery of excavation, emptiness and darkness, before I even entered the CFT. This meant I felt at home at the consortium’s construction sites. Agamben’s words seem to look back to my past; I’ve worked extensively in Anatolia, Cappadocia, archaic Egyptian tombs, and the buried landscapes of the fringes of Aztec Mexico. I started my journey by learning to use a 20×25 view camera in the parking lots of New York’s Lower East Side in the early 2000s, but subsequently I’ve always sought something original, fresh, a first. In my final year at the School of Visual Arts I decided to skip all the Photoshop courses, devoting myself instead to colour printing in the darkroom. The transition from the colour darkroom on Manhattan’s 22nd Street to Europe’s historiated caves isn’t something that surprises me today, looking back twenty years; we all have a latent image within us, which takes its time to develop.

AD: From the caves that have preserved the oldest human traces on Earth in darkness for thousands of years to the tunnels of the new Naples-Bari high-speed railway line, which has opened underground passages in the landscape to bring contemporary humans closer to the future.

DM: The thing that strikes me most about the tunnels is the sound of the construction site, the echo of work, the undercurrent of time, of digging through time. In some of the pictures I tried to portray this sense of the depth and curvature of space and time that the tunnel conveyed. This stage of excavating the mountain, of crossing it to alter space-time, is perhaps the essence of my work, something that sucks you in and suddenly transports you far away to an unpredictable elsewhere at a crazy speed. I’ve seen the digging, the dust, the work and the sound as this collective ambition to cross the uncrossable; that’s what these tunnels do, remove us from the name, the present, the place. In the end I always arrive at abstraction.

AD: The work collected in this book runs right through your entire imagery. In your photographs of the construction site, I saw the Hartapu monument in Kızıldağ again, the engraving of the auroch in Papasidero, the wall of the cemetery in San Giovanni Galermo and the graffiti-covered wall in Milan.

DM: I tried to make a personal work, as an artist, with the photograph itself reflected in time, curving round until its ends meet and disappearing into the concave space. That’s why clues are crucial in this puzzle, clues as images, keys to my journey – not my photographs, but the images that made them possible. There are basically two of them, then a third image, essentially forming a triangle. In May 2022, I wanted to visit the city of Benevento with my girlfriend Francesca before returning to the tunnels. I thought it was important to see the oldest city near the construction sites. Caught in a sudden downpour, we took shelter under Trajan’s Arch in the city centre. While we were under the arch, I discovered a strange, faint engraving of a horse, which was very delicate and beautiful, and I decided to photograph it with the big view camera – the camera was bigger than the drawing itself. It was undoubtedly an historical engraving, from perhaps 100, 200, 300 or even 1,000 years ago, who knows? But never mind its archaeological value, let’s return to the pure image: an arch that creates an imaginary bridge, in which, in its innermost part, there resides an animal, a Spiritus Rector, a guardian of the arch or, as they say in Ghostbusters, a gatekeeper. It was perhaps only a year later, towards the end of my visits to the CFT, that I discovered that there’s a rampant horse on all the workers’ placemats in the canteen. Actually, it’s much more than a horse, it’s the skeleton of a rampant horse. Perhaps it’s the protective spirit of the tunnel, the workers and the construction site that tries to pierce space and time like my photographs? A rampant horse also adorns the cutlery holder, containing the utensils to feed the consortium’s entire workforce; it’s dead – a skeleton – but it always resurrects, at lunch and dinner each day. We are left with the simple truth of the image: a horse that comes to life and bolts from the world of the dead, from the underworld to us. I’d seen a similar horse in Harry Potter, and it was also winged! It was invisible to everyone except Harry and his friend Luna, endowed with a strange ability to see ghosts, just like Harry, who was also initiated into mysteries that are forbidden to us. In between visits to the CFT, I also happened to have the good fortune to return to a cave I know very well, at Monte Castillo in northern Spain. It’s a triangular mountain that’s home to numerous caves, engravings, drawings and depictions of the earliest images in human history. I had been to Monte Castillo many times, but on this visit accompanied by Eduardo and Francesca we reached the point in the cave where I was convinced it ended. It’s a special, very deep place, where the stalactites and stalagmites are almost completely soaked in red ochre and where it really seems you can’t go any further beyond a precipice and a ditch. However, that day I discovered that there’s a little path that goes a few dozen metres further, and that it’s not the end of the cave; the end isn’t the real end. I also discovered that there are small carvings on the floor like nowhere else in the cave, a drawing of a pair of horses, and a lone horse at the end of the space, at the end of time.

AD: Reflection on the depiction of the construction site gradually overlapped with reflection on photography. To use Agamben’s words, that direct link that mysteriously connects the cave to the spirit, and the sky to the mind, led you from the symbolism of the cave to pure abstraction. A transition that’s also marked by the use of your phone camera as a visual notebook. It’s probably a kind of liberation after all these years in the darkness of the darkroom.

DM: Working in the darkness of caves so close to 40,000-year-old drawings has certainly changed something inside me. The complete lack of movement, the compression and the difficulties of the view camera that I’d imposed on myself in the caves, made my language abstract. The prehistoric experience liberated me from myself, putting me in touch with a bigger picture. I have hundreds of photographs taken with my iPhone that don’t depict anything… or so it would seem. In a way, they gathered themselves, as preparatory images of a highly imaginative organism. It all happened listening to music and walking in the contemporary world with the prehistoric images still in my heart. I asked myself what the future image might be? The deep past prompted me to imagine our future. I started to make room for simple signs and colours, lines and flashes on walls, surfaces, doors, boundaries of many realities. I see many of these files as “preparatory drawings”, like a game. Photography can be drawing, it can be painting, it can be what it is: Pure Image.

AD: Beneath the artificial light of the tunnel, you managed to connect two seemingly distant sides of photography: documentation on the one hand and abstraction on the other.

DM: Everything is curved and connected by a tunnel that, like a circle, reminds us that we live on the surface of a burning sphere, covered with water and earth, which floats in the darkness and moves in the light.

1 Giorgio Agamben, Quel che ho visto, udito, appreso… (Turin: Einaudi, 2022).

Una conversazione tra Domingo Milella e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Nelle necropoli della Tuscia, nelle chiese scavate nella roccia in Cappadocia e, molti anni prima, a Lascaux ho visto che fra la caverna e lo spirito vi è un nesso immediato, altrettanto forte di quello che unisce il cielo alla mente.1

AD: Le poche righe che abbiamo scelto come introduzione alla nostra conversazione tracciano una parabola che sintetizza la tua ricerca artistica negli ultimi venti’anni con quella semplicità e quella chiarezza che ci riempiono di stupore ogni volta che incontriamo i nostri pensieri nelle parole di altri.

DM: Sono otto anni che mi occupo di caverne e arte preistorica. Quindi questo rapporto con la grotta e con il primitivo, l’immaginario dello scavo, del vuoto e del buio, mi apparteneva già prima di entrare al CFT. Nei cantieri del consorzio mi sono quindi sentito a casa. Le parole di Agamben sono retro-veggenti a modo loro; ho lavorato molto in Anatolia, in Cappadocia, nelle tombe dell’Egitto arcaico, nei paesaggi sepolti delle periferie del Messico Azteco. Ho iniziato il mio viaggio imparando a usare il banco ottico 20×25 nei parcheggi del Lower East Side a New York nei primi anni Duemila, ma poi ho sempre cercato qualcosa di originario, di primo, di sorgivo. Decisi nel mio ultimo anno alla School of Visual Arts di saltare tutti i corsi di Photoshop e d’immergermi invece nella stampa a colori in camera oscura. Il passaggio dalla “color dark-room” sulla ventiduesima strada a Manhattan alle grotte istoriate d’Europa non è una cosa che oggi, ripensando a vent’anni fa, mi sorprende; tutti abbiamo un’immagine latente dentro di noi, che richiede il suo tempo per svilupparsi.

AD: Dalle caverne che hanno custodito per migliaia di anni nell’oscurità le più antiche tracce dell’uomo sulla Terra ai tunnel della nuova linea ferroviaria ad alta velocità Napoli-Bari, che aprendo varchi sotterranei nel paesaggio, avvicinano l’uomo di oggi al futuro.

DM: La cosa che mi colpisce di più dei tunnel è il suono del cantiere, l’eco del lavoro, il sottofondo del tempo, dello scavo nel tempo. In alcune immagini ho provato a ritrarre questo senso del profondo e della curvatura dello spazio e del tempo che la galleria trasmetteva. Questo stadio dello scavare la montagna, di attraversarla per modificare lo spazio-tempo, forse è il nocciolo del mio lavoro, qualcosa che ti risucchia e improvvisamente ti trasporta lontanissimo e in un’imprevedibile altrove a una velocità senza senso. Ho visto lo scavo, la polvere, il lavoro e il suono come questa collettiva ambizione di travalicare l’intravalicabile… magari è una parola che non esiste neanche, ecco cosa fanno questi tunnel: portano fuori dal nome, dal presente, dal dove. Alla fine approdo sempre all’astrazione, che mi sono spesso domandato, è azione delle stelle?!

AD: Il lavoro raccolto in questo libro ripercorre trasversalmente tutto il tuo immaginario. Nelle tue fotografie del cantiere ho rivisto il monumento di Hartapu a Kızıldağ e l’incisione del Bove Primigenio di Papasidero, ho rivisto il muro di cinta del cimitero di San Giovanni Galermo e la parete ricoperta di graffiti a Milano.

DM: Ho provato a fare un lavoro personale, come artista, che con la fotografia si riflettesse nel tempo curvandosi sino a fermarsi su sé stesso e a scomparire nello spazio concavo. Per questo sono cruciali gli indizi in questo enigma, indizi come immagini, chiavi del mio viaggio – non le mie fotografie, ma le immagini che le hanno rese possibili. Sono essenzialmente due, poi una terza immagine, a formare fondamentalmente un triangolo. A Maggio del 2022 prima di tornare nei tunnel ho voluto visitare con la mia fidanzata Francesca la città di Benevento. Trovavo fosse importante vedere il centro più antico vicino ai cantieri. A causa di una grande pioggia improvvisa ci siamo riparati sotto l’arco di Traiano che si trova al centro della cittadina. Mentre eravamo lì sotto ho scoperto una strana e pallida incisione di un cavallo, molto bella, molto leggera, ed ho deciso di fotografarla con il grande banco ottico – la macchina fotografica era più grande del disegno stesso. Un’incisione storica certo, di forse 100, 200, 300 o anche 1.000 anni fa, chi lo sa? Ma non importa il suo valore archeologico, torniamo all’immagine pura: un arco che crea un ponte immaginario, dentro il quale, parte più intima, risiede un animale, uno Spiritus Rector, un guardiano dell’arco, o come dicono in Ghostbuster, un guardiano di porta… Forse solo un anno dopo, verso la fine delle mie visite al CFT scopro che sulla tovaglietta della mensa di tutti i lavoratori è impresso un cavallo – rampante. Per essere esatti, è molto di più di un cavallo: è lo scheletro di un cavallo rampante. Forse l’anima protettrice del tunnel, dei lavoratori e del cantiere che tenta, come le mie fotografie, di perforare lo spazio e il tempo? Un cavallo rampante adorna anche il contenitore delle posate, strumenti per la nutrizione di tutta la manodopera del consorzio; è morto, è uno scheletro, ma risuscita sempre, ogni giorno, a pranzo e a cena. Rimaniamo con la semplice verità dell’immagine: è un cavallo che giunge vivo e imbizzarrito dal mondo dei morti, dal sottomondo a noi. Avevo visto un cavallo simile in Harry Potter, peraltro era alato! Era invisibile a tutti, tranne ad Harry e alla sua amica Luna, anch’essa dotata di una strana capacità di vedere i fantasmi, proprio come Harry, iniziato anche lui a Misteri a noi preclusi. Tra una visita e l’altra al CFT mi capita di avere la fortuna di tornare in una grotta che conosco molto bene, al monte Castillo nel nord della Spagna. Una montagna triangolare che contiene numerose grotte, incisioni, disegni e rappresentazioni delle prime immagini della storia dell’uomo. Ero stato tante volte al Castillo, ma in occasione di questa visita in compagnia di Eduardo e Francesca arriviamo nel punto in cui ero convinto che la caverna finisse. È un luogo particolare, molto profondo, dove le stalattiti e le stalagmiti sono quasi completamente imbevute di ocra rossa e dove oltre un dirupo e un fosso sembra davvero non si possa andare avanti. Invece scopro quel giorno che esiste un piccolo sentiero che prosegue per altre decine di metri e che la fine della caverna non è quella; la fine non è la vera fine. Scopro inoltre che come in nessun’altra parte della grotta, esistono delle piccole incisioni sul pavimento: un disegno di una coppia di cavalli – e un cavallo solitario al fondo dello spazio, al fondo del tempo.

AD: La riflessione sulla rappresentazione del cantiere si è progressivamente sovrapposta alla riflessione sulla fotografia. Per dirla con le parole di Agamben, quel nesso immediato che misteriosamente unisce la caverna allo spirito e il cielo alla mente ti ha condotto dal simbolismo della grotta alla pura astrazione. Un passaggio segnato anche dall’uso della fotocamera del telefono come quaderno di appunti visivi. Probabilmente una sorta di liberazione dopo tutti questi anni nell’oscurità della camera oscura.

DM: Sicuramente l’aver lavorato nel buio delle grotte così vicino a disegni di 40.000 anni fa, ha cambiato qualcosa dentro di me. La totale mancanza di movimento, la compressione e le difficoltà del banco ottico che mi ero imposto di usare nelle caverne, hanno reso astratto il mio linguaggio. L’esperienza preistorica mi ha liberato da me stesso, mettendomi in contatto con un disegno più grande. Ho centinaia di fotografie fatte con l’iPhone che non ritraggono nulla… o almeno così sembrerebbe. In un certo senso, si sono raccolte da sole, come immagini preparatorie di un organismo immaginifico. Tutto è avvenuto ascoltando la musica e camminando nel mondo contemporaneo con ancora le immagini preistoriche nel cuore. Mi domandavo: quale potrebbe essere l’immagine futura? Il profondo passato mi ha spinto a immaginare il nostro avvenire. Ho cominciato a dare spazio a semplici segni e colori, linee e bagliori su muri, superfici, porte, confini di tante realtà. Molti di questi file li vedo come “disegni preparatori”. La Fotografia può essere disegno, può essere dipinto, può essere quel che è: Immagine Pura.

AD: Sotto la luce artificiale del tunnel, sei riuscito a collegare due versanti apparentemente lontani della fotografia: da un lato la documentazione e dall’altro l’astrazione.

DM: Tutto è curvo e collegato da un tunnel che, come un cerchio, ci ricorda che viviamo sulla superficie di una sfera rovente, coperta di acqua e terra, che fluttua nel buio e si muove nella luce.

1 Giorgio Agamben, Quel che ho visto, udito, appreso…, Einaudi, Torino 2022.

Luca Nostri and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

AD: Unlike the construction sites visited by the other authors featured in this collection, work on the Matanza-Riachuelo Basin, one of the most complex wastewater purification projects in the world, was almost finished when you arrived in Buenos Aires. The new network of tunnels had been completed and the main wells were about to be sealed. Travelling along the banks of the Rio Matanza-Riachuelo to its mouth in the Rio de la Plata, between the barrio of La Boca and the town of Dock Sud, was the only way to “see” the invisible infrastructure that will improve the quality of life of over 14 million people in the coming years.

LN: When I was assigned the Buenos Aires construction site, I was immediately struck by the imagery of the Riachuelo River, which runs through the city and flows into the Rio de La Plata, opposite Uruguay, and which is unfortunately mainly known for its pollution and associated problems, with serious consequences for the inhabitants of some of the city’s critical districts. I have always been interested in the geographical and topographical exploration of an area, which limits my work but also helps to guide it, and is usually a good excuse to go out and take photographs. With this in mind, I started by looking back over some books, including The Red River by Jem Southam, who was my tutor at Plymouth for my PhD. Although The Red River is set in a rural area, there are many similarities in the sequence of 50 photographs following a watercourse in west Cornwall, from source to sea, which passes through different areas. The entire river valley has been extensively mined for tin and copper ore for hundreds of years, and it is the extraction of water from the mine and its use to crush the ore that stains the river red. It is also a work that combines views of the river with interiors of houses and photographs of the villages the river flows through. I have also used this strategy of photographing both the river and the inhabited areas near it.

AD: Exploring a bookshelf is the best first step of any journey. On mine, I found some passages that remind me of your way of taking photographs in a book by Robert Adams entitled Along Some Rivers: Photographs and Conversations. In particular, in the transcript of his opening speech at a debate held at the Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco, Adams mentions the two qualities he always looks for in people and in the art they create, collect or admire: a sense of urgency and faithful accuracy. Faithfulness (often in contrast to originality) seems to me a possible key to your work.

LN: Along Some Rivers is a book of some of Adams’s conversations with various curators and includes a largely unpublished sequence of 28 photographs along the Rio Grande and Columbia River, following human traces in the landscape. When Robert Adams talks about faithfulness, or the search for some form of truth, he’s not talking about merely descriptive, or topographical, accuracy of the real world. The goal, he says, “is to face facts but to find a basis for hope. To try for alchemy”. It’s another way of rephrasing one of his most famous and much-quoted statements: “Landscape pictures can offer us, I think, three verities — geography, autobiography and metaphor. Geography is, if taken alone, sometimes boring; autobiography is frequently trivial; and metaphor can be dubious. But taken together… the three kinds of information strengthen each other and reinforce what we all work to keep intact — an affection for life.” This “alchemy” is of course sometimes achieved and sometimes not, but it is certainly a very inspiring approach. What I appreciate about Adams’s essays and interviews is that they are unencumbered by postmodern attitudes and theorizing, and each time I pick them up they make me want to take photographs. I realize now, flipping through Along Some Rivers, that Adams’s photographs are all vertical and in hindsight, perhaps, I should have done the same.

AD: The vertical format of Adams’s photographs allows us to introduce a distinctive aspect of your book: the orientation of the pictures in the sequence is always vertical regardless of the orientation of their subjects.

LN: The Columbia River is the same river photographed by Carleton E. Watkins in Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon, one of my reference works. The crystal clarity of the photographs is impressive. There is a very beautiful and now hard-to-find book of this work from which I took the idea of “turning the photographs” for the final sequence: the format of the book is in fact horizontal, as are almost all the photographs, but the final sequence ends with four vertical landscapes – the silhouette of a mountain on a lake and three waterfalls – that are laid out on the page. The visual transition from horizontal to vertical, playing on the horizon line, is very subtle and delicate, but also very powerful, offering the opportunity for a more abstract and formal interpretation of the photographs. This idea inspired me to construct the sequence, considering the necessarily vertical format of the book. One of the things that struck me, arriving at the site of the sole well still open, was its size, in terms of both diameter and depth. The sensation of dizziness was very strong. Additionally, due to the depth and the black concrete blocks, on a normal sunny day the contrast of light between the illuminated part, and deep part in shadow, is too high and the film is unable to record both extremes. This is the reason why the line of the well, which in some photographs I have kept very high up in the shot, becomes a kind of horizon of photographic events, below which there is a kind of total darkness, an abyss. The idea of “rotating” the image on the page by placing it vertically was also to elicit or reinforce the sensation of dizziness.

AD: Let’s resume our back and forth of books.

LN: Another book that I think is very important, although little known, is The Subdury River: A Celebration by Frank Gohlke, published in 1993. It resonates with me because Gohlke uses the 13×18 colour format, which I also use a lot. The work has a biographical basis, for the photographer takes an interest in the river near his new home after moving to Massachusetts, setting in motion that process of discovery and creation through which we come to feel at home in our own particular parts of the world. In some ways I too, as a visiting outsider, used the Riachuelo to get to know Buenos Aires, instead of starting with the city’s “highlights” as a normal tourist would. And despite being “foreign” to the city, I sought an intimate viewpoint with certain areas of the river that I’d insisted on, rather than pursuing the visuals and modus operandi of the epic exotic journey. That’s why another reference I had in mind was Fiume (River) by Guido Guidi.

AD: Fiume is a compilation of a series of shots of the river that flows a few hundred metres from Guidi’s home in Cesena. The relationship with the everyday landscape, with that area that begins immediately beyond his doorstep, reminds us of the Senio and Santerno rivers that flooded the town and countryside of Lugo, one of the municipalities most affected by the floods in Emilia Romagna, where you grew up and where your family also lives.

LN: The flooding in Emilia-Romagna last May was as shocking as it was unexpected. I was at my grandparents’ house the morning it happened, and I’ll never forget the sight of the water slowly crossing the threshold. And the water as far as the eye could see across the open, flat landscape. The reasons for the floods are complex and manifold; certainly there were a number of concurrent unfortunate circumstances, and some have spoken of a “perfect storm”, but one of the main issues is undoubtedly the management of the rivers, riverbanks and land. This brings us directly back to the work on the Ghella construction site to relieve the Riachuelo river, which is at constant risk of flooding in certain neighbourhoods: as you said at the beginning, it’s a project that is as useful as it is invisible. I’m reminded of a comment by the painter and writer Christopher Neve in a book entitled Unquiet Landscapes (recently recommended to me by my friend John Spinks) about the painter John Nash, whose method of working could be compared to that of a water-diviner who “does not actually alter anything but who has some odd quality, that enables him to hint at what may be hidden, just by looking for places and objects which carried for him a particular charge”. After all, even good photography is a kind of perfect storm.

Una conversazione tra Luca Nostri e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

AD: A differenza dei cantieri visitati dagli altri autori coinvolti in questa raccolta, il cantiere del bacino Matanza-Riachuelo, uno dei progetti di depurazione di acque reflue più complessi al mondo, al tuo arrivo a Buenos Aires era ormai quasi concluso. La nuova rete di tunnel era stata completata e i pozzi principali stavano per essere sigillati. Percorrere le sponde del Rio Matanza-Riachuelo fino alla sua foce nel Rio de la Plata, tra il barrio di La Boca e la città di Dock Sud, era l’unico modo per “vedere” un’infrastruttura invisibile che nei prossimi anni migliorerà la qualità di vita di oltre 14 milioni di persone.

LN: Quando mi è stato affidato il cantiere di Buenos Aires sono subito rimasto colpito dall’immaginario del fiume Riachuelo, che attraversa la città e sbocca sul Rio de La Plata, di fronte all’Uruguay, e che purtroppo è noto per lo più per problemi legati all’inquinamento, con gravi conseguenze sugli abitanti di alcuni quartieri critici della città. Mi è sempre interessata l’esplorazione geografica e topografica di un territorio, che mette dei confini al lavoro ma anche aiuta a pilotarlo, ed è di solito un’ottima scusa per uscire a fotografare. Con queste premesse, sono partito riguardando alcuni libri, tra cui The Red River di Jem Southam, che è stato mio tutor a Plymouth per il PhD. The Red River è ambientato in un territorio rurale, ma i punti di contatto sono molti: una sequenza di cinquanta fotografie che segue un corso d’acqua nell’ovest della Cornovaglia, dalla sorgente al mare, e che attraversa aree di diversa natura. L’intera valle del fiume è stata ampiamente sfruttata per centinaia di anni al fine di estrarne stagno e rame, e sono stati appunto l’estrazione dell’acqua dalla miniera e il suo utilizzo per frantumare il minerale a macchiare il fiume di rosso. Inoltre è un lavoro che mette insieme vedute del fiume, interni delle case e fotografie dei paesi attraversati dal fiume. Ho utilizzato anche’io la strategia di fotografare sia il fiume che le zone abitate nei suoi pressi.

AD: L’esplorazione di una libreria è il miglior primo passo di ogni viaggio. Nella mia, in un libro di Robert Adams dal titolo Along Some Rivers. Photographs and Conversations, ho ritrovato alcuni passaggi che mi parlano del tuo modo di fotografare. In particolare, nella trascrizione del suo discorso di apertura di un dibattito tenutosi alla Fraenkel Gallery di San Francisco, Adams indica le due qualità che cerca sempre nelle persone e nell’arte che esse creano, collezionano o ammirano: una sensazione di urgenza e una fedele esattezza. La fedeltà (spesso in contrapposizione all’originalità) mi sembra una possibile chiave di lettura del tuo lavoro.

LN: Along Some Rivers è un libro che raccoglie alcune delle conversazioni di Adams con diversi curatori, e include una sequenza per lo più inedita di 28 fotografie scattate lungo il Rio Grande e il Columbia River, seguendo le tracce dell’uomo nel paesaggio. Quando Robert Adams parla di fedeltà, o della ricerca di una qualche forma di verità, non parla di una mera esattezza descrittiva, o topografica, del mondo reale. L’obiettivo, dice, “è affrontare i fatti, ma per trovare una base per la speranza. Tentare l’alchimia”. È un altro modo di riformulare una delle sue più famose e citate affermazioni: “Le immagini di paesaggio possono presentarci tre verità: la verità geografica, quella autobiografica e quella metaforica. La geografia di per se stessa è a volte noiosa, l’autobiografia spesso banale, e la metafora può essere equivoca. Ma presi insieme… questi tre tipi di informazione si rafforzano a vicenda e alimentano ciò che tutti cerchiamo di mantenere intatto: l’attaccamento alla vita”. Questa “alchimia” naturalmente a volte si crea e a volte no, ma di certo è un approccio di grande ispirazione. Ciò che apprezzo dei saggi e delle interviste di Adams è che sono liberi da atteggiamenti e teorizzazioni postmoderne, e ogni volta che li riprendo in mano mi fanno venire voglia di fotografare. Realizzo ora, sfogliando Along Some Rivers, che le fotografie di Adams sono tutte verticali e col senno di poi, forse, avrei dovuto fare lo stesso.

AD: La verticalità delle fotografie di Adams ci permette di introdurre un aspetto peculiare del tuo libro: l’orientamento delle immagini nella sequenza è sempre verticale a prescindere dall’orientamento dei loro soggetti.

LN: Il Columbia River è lo stesso fiume fotografato da Carleton E. Watkins in Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon, una delle mie opere di riferimento. La chiarezza cristallina delle fotografie è impressionante. Di questo lavoro esiste un libro molto bello e ormai difficile da trovare da cui ho preso l’idea di “girare le fotografie” per la sequenza finale: il libro infatti è di formato orizzontale, come quasi tutte le fotografie, ma la sequenza finale si chiude con quattro paesaggi verticali, il profilo di una montagna su un lago e tre cascate. Il passaggio visivo dall’orizzontalità alla verticalità, giocando sulla linea dell’orizzonte, è molto sottile e delicato, ma anche molto potente, e consente di interpretare le fotografie in modo più astratto e formale. Mi sono ispirato a questa idea per costruire la sequenza, considerando il formato necessariamente verticale del libro. Una delle cose che mi ha colpito, arrivando sul cantiere dell’unico pozzo ancora aperto, è stata la sua dimensione, sia per diametro che per profondità. La sensazione di vertigine era molto forte. Inoltre, a causa della profondità e dei blocchi di cemento di colore nero, in una normale giornata di sole il contrasto di luce tra la parte illuminata, e quella in ombra in profondità, è troppo elevato e la pellicola non riesce a registrarne entrambi gli estremi. Per questo motivo la linea del pozzo, che in alcune fotografie ho tenuto molto in alto nell’inquadratura, diventa una sorte di orizzonte degli eventi fotografici, al di sotto del quale si finisce in una sorta di buio totale, di abisso. L’idea di “ruotare” l’immagine sulla pagina, mettendola in verticale, era anche quella di suscitare o rinforzare la sensazione di vertigine.

AD: Continuiamo il nostro ping pong bibliografico.

LN: Un altro libro che ritengo molto importante, anche se poco conosciuto, è The Subdury River. A celebration di Frank Gohlke, pubblicato nel 1993. Questo lavoro mi coinvolge perché Gohlke utilizza il formato 13×18 a colori, che uso molto anch’io. Il lavoro ha delle premesse biografiche: il fotografo si interessa al fiume vicino alla sua nuova casa, dopo essersi trasferito nel Massachusetts, e attiva quel processo di scoperta e creazione attraverso il quale arriviamo a sentirci a casa nelle nostre specifiche parti del mondo. In qualche modo anche io, da visitatore esterno, ho utilizzato il Riachuelo per prendere confidenza con Buenos Aires, invece di partire dagli “highlights” della città come farebbe un normale turista. E nonostante il mio essere “alieno” alla città, ho cercato un punto di vista intimo con alcune zone del fiume sulle quali ho insistito, invece di cercare l’estetica e il modus operandi del viaggio epico ed esotico. Ecco perché un altro riferimento che avevo in mente era Fiume di Guido Guidi.

AD: Fiume raccoglie una serie di fotografie del fiume che scorre a poche centinaia di metri dall’abitazione di Guidi a Cesena. Il rapporto con il paesaggio quotidiano, con quel territorio che inizia immediatamente oltre la soglia di casa, ci rimanda ai fiumi Senio e Santerno, i corsi d’acqua che a causa del maltempo sono straripati allagando il centro e le campagne di Lugo, uno dei comuni più colpiti dall’alluvione dell’Emilia Romagna, dove sei cresciuto e dove vive anche la tua famiglia.

LN: L’alluvione dello scorso maggio in Emilia-Romagna è stata una esperienza scioccante quanto inaspettata. Ero a casa dei miei nonni la mattina in cui è arrivata, e l’immagine dell’acqua che lentamente varca la soglia di casa non la dimenticherò mai. Così come quella dell’acqua a perdita d’occhio nel paesaggio aperto e pianeggiante. Le ragioni di quello che è successo sono complesse e molteplici; di sicuro ci sono state una serie di circostanze sfortunate concomitanti, e qualcuno ha parlato di “tempesta perfetta”, ma uno dei temi principali è senza dubbio la gestione dei fiumi, degli argini e del territorio. Questo ci riporta direttamente all’intervento del cantiere Ghella di alleggerimento del fiume Riachuelo, che in alcuni quartieri è costantemente a rischio esondazione: come dici all’inizio del testo, è un intervento tanto utile quanto invisibile. Mi viene in mente un commento del pittore e scrittore Christopher Neve in un libro dal titolo Unquiet Landscapes (consigliatomi di recente dal mio amico John Spinks) a proposito del pittore John Nash, il cui metodo di lavoro potrebbe essere paragonato a quello di un rabdomante che “in realtà non altera nulla, ma che ha una qualche strana capacità che gli consente di cogliere ciò che potrebbe essere nascosto, semplicemente cercando luoghi e oggetti che avevano veicolato per lui una particolare ‘carica”. In fondo, anche una buona fotografia è una sorta di tempesta perfetta.

Giulia Parlato and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

The world is blue at its edges and in its depths. This blue is the light that got lost.1

AD: Examining the hundreds of pictures from the company’s construction sites, mostly photographs documenting the states of progress and key moments in the life of the sites, allowed us to pick out imagery relevant to the work of the artists involved. Each of the photographers was associated with a particular site, considering the possible directions that various artistic approaches could take in each of the scenarios. The intention was in fact to use the construction sites as a source of inspiration for an unprecedented series of visual adventures. However, in your case, things turned out differently.

GP: Yes, that’s true. When you told me that Auckland was one of the possible destinations, it seemed like an unmissable opportunity for me to finally visit a place that’s always been part of my family history. A place that over the years has assumed fantastical traits, due to both the stories and its geographical remoteness. I grew up listening to my great-grandmother Giulia’s stories, one of which was about her son Francesco, who disappeared in New Zealand in the 1964. Francesco had travelled a lot, moving many times in search of himself. He spoke several languages, painted and wrote poetry, and had an inquisitive but melancholy nature. After having worked for a few years at a local newspaper called The Auckland Star, he decided to move to Taupaki, a town a few kilometres north-west of Auckland. He grew roses in his garden and planned to build a greenhouse. Then one day he vanished. At home we kept the letters, poems, dried flowers, paintings, photographs and postcards he’d sent to his family in Sicily.

AD: The imagery of 1960s New Zealand and the memories of your far-off great-uncle created a particular atmosphere, a platform on which you built your own idea of the project in terms of the technical specifications of the site, the implications for the natural landscape and relations with the Māori communities.

GP: New Zealand immediately strikes you with its spectacular, unspoiled natural landscapes in which to lose yourself. Taking the aesthetic aspect of the visual material left by Francesco as my starting point, I chose to explore the landscape and geological features that distinguish the excavation work, using colour photography and a view camera. Moving away from my usual method of working, I limited my research to the bare essentials before starting to take photographs. Once I’d identified the main elements that I knew would be my starting point, I chose to be guided by the people I’d meet, the things that would intrigue me along the way and the stories I’d discover. The focus on preserving the area’s biodiversity and the numerous projects to restore the landscape that will follow these excavation works are impressive. I’m not just talking about the effects strictly related to the construction of the tunnel, but also to those regarding the volcanic island of Puketutu, where the earth extracted from the underground construction site is transported. Before it was exploited and irremediably transformed to build Auckland airport, Puketutu was a sacred place for the Māori. The new construction site has allowed the island’s original appearance to be restored. In short, the highly organized, technological, artificial excavation sites scattered throughout the city are in perfect harmony with the surrounding natural landscape, forming part of a construction and reconstruction project that is, in my opinion, cultural more than anything else. The historical authenticity of a place is the key through which my photographic work takes shape. I’m interested in the fragments of a distant, forgotten past. Partial clues and all that is hidden or missing are often the subjects of my pictures.

AD: Your first-hand experience of the site yielded a series of impressions that helped shape your visual approach. In our exchanges you repeatedly used Captain Nemo’s Nautilus as an evocative analogy of being inside the tunnel and the TBM. Searching online, I discovered that, in addition to being the name of the submarine that appears in Jules Verne’s novels Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and The Mysterious Island, Nautilus was also the name of the first underwater boat built in 1800 and the first nuclear-powered submarine built in 1954. The word nautilus comes from the name of an extraordinary marine creature, an ancient mollusc that inhabits a spiral shell and has a primitive visual system: its eye functions like a pinhole camera, whereby focus works at the expense of brightness and vice versa; all aspects that I later found in your pictures.

GP: Before I got there, I hadn’t really grasped the site’s extraordinary dimensions. In order to reach the main TBM, I had to descend by lift via one of the shafts from which the freshly extracted spoil was constantly transported. The tunnel commenced at the bottom. There was a little train but I decided to walk so that I could stop and take photographs. I walked about two kilometres before I saw the excavation face. At first in silence and then accompanied by mechanical noises, voices and laughter. For anyone unaccustomed to such scenarios, finding yourself in the construction site of a tunnel under the sea conjures up sci-fi fantasies. When you arrive at the TBM, you really feel as though you’re in a submarine. There are several floors, a computer room, all sorts of scaffolding, cables and devices. The many people who work there, move almost in unison, at ease, passing each other materials, tools or a coffee. The term nautilus effectively sums up the atmosphere of this work. It refers not only to the concept of adventure and discovery but also to the tunnel and the submarine, the bird’s-eye views and the forests, the mysteries of the Earth and palaeontology. After all, the still-lifes with fossils that I photographed at the Auckland War Memorial Museum are the real protagonists of this story.

AD: In the book, pictures of the shells and marine fossils found at the construction site are alternated with glimpses of the tunnel and the site itself, views of Auckland, the coastline and the unspoiled natural landscape, particularly the island of Puketutu.

GP: The sequence we’ve chosen for the book is a round trip across the landscape of Auckland and the construction site, from the sky to below ground. The choice to contrast the features of the construction site with the surrounding natural scenery was prompted by observing the similarity between the spoil extracted from the tunnel and transported to Puketutu for the reconstruction of the original scoria cones and the area’s rocks and volcanic sand beaches. The few human figures appear distant and lost in sweeping landscapes, while the fossils are described up close, viewed like prehistoric creatures swimming in the sea. And so, as in my previous works, materials are key. Materials that change texture, shape, geographical location, historical meaning and cultural significance before our eyes.

AD: The relationship with your artistic research and practice, materials, memory, invisibility and rediscovery: everything seems to bring us back to your personal story. A series of coincidences – some unexpected, others sought – probably aligned to show you the way towards a new work.

GP: My fascination with history and rediscovering the past, with what is distant, submerged or invisible, certainly has something to do with the time I spent listening to my great-grandmother Giulia. She was a great storyteller. She’d tell me about her childhood and the games she played with her many cousins, about her absent and distant father, about when the Germans burned her house down during the Second World War and her long journey across Italy with her children. Ever since I was a child, all of these things have led me to wonder about the imaginative power of storytelling, the way we tell the past and how it is told to us by others. Francesco and I never met, yet I was thrilled to take his map of Auckland – on which he’d made notes to show his parents where he lived and the places he frequented – back to the city. His story deals with issues very close to me, which I intend to explore further. I’ve just started to work on a new project that focuses on the act of vanishing and on landscape as testimony, and which was spawned by the musings and notes that I took during my trip to New Zealand. I’m happy that I’ll soon start photographing again.

1 Rebecca Solnit (2017), A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Edinburgh, Canongate Books.

Una conversazione tra Giulia Parlato e Alessandro Dandini de Sylva

Il mondo è blu ai suoi margini e nelle sue profondità. Questo blu è la luce che si è persa.1

AD: Lo studio delle centinaia di immagini provenienti dai cantieri dell’azienda, perlopiù fotografie che documentano i progressivi stati di avanzamento e i momenti decisivi nella vita dei cantieri, ci ha permesso di scorgere immaginari rilevanti per le ricerche degli artisti coinvolti. Ciascuno degli autori è stato associato ad un particolare cantiere, valutando le possibili derive che differenti pratiche artistiche avrebbero potuto prendere in ognuno dei contesti. L’intento era proprio quello di usare i cantieri come fonte di ispirazione per una inedita serie di avventure visive. Con te, però, le cose sono andate in modo diverso.

GP: Sì, è vero. Quando mi hai detto che Auckland era una delle possibili destinazioni, mi è sembrata un’occasione imperdibile per visitare finalmente un luogo che ha sempre fatto parte della mia storia familiare. Un luogo che nel tempo, sia per i racconti sia per la lontananza geografica, ha assunto tratti fantasmatici. Sono cresciuta ascoltando le storie della mia bisnonna Giulia. Una di queste è la storia di suo figlio Francesco, scomparso in Nuova Zelanda nel 1964. Francesco aveva viaggiato molto, spostandosi spesso, alla ricerca di sé stesso. Parlava diverse lingue, dipingeva, scriveva poesie. Era un curioso ma anche una persona malinconica. Dopo aver lavorato per qualche anno per il giornale locale “Auckland Star”, decise di trasferirsi a Taupaki, una località pochi chilometri a nord-ovest di Auckland. Coltivava rose nel giardino di casa e progettava di costruire una serra. Poi un giorno scomparve. In casa abbiamo conservato fotografie, cartoline, lettere, poesie, fiori essiccati e dipinti che Francesco spediva ai suoi familiari in Sicilia.

AD: L’immaginario della Nuova Zelanda degli anni Sessanta e i ricordi del tuo lontano prozio hanno determinato una particolare atmosfera, un plateau su cui hai costruito una tua idea del lavoro in relazione alle caratteristiche tecniche del cantiere, alle implicazioni per il paesaggio naturale e al rapporto con le comunità Māori.

GP: La Nuova Zelanda colpisce subito per gli spettacolari ed incontaminati paesaggi naturali in cui perdersi. Partendo dall’estetica del materiale visivo lasciato da Francesco, ho scelto di esplorare gli aspetti paesaggistici e geologici che contraddistinguono questa campagna di scavi, utilizzando la fotografia a colori e il banco ottico. Allontanandomi dal mio usuale metodo di lavoro, ho limitato all’essenziale la ricerca prima di iniziare a fotografare. Una volta individuati gli elementi principali che sapevo avrebbero costituito il mio punto di partenza, ho scelto di farmi guidare dalle persone che avrei incontrato, da ciò che mi avrebbe affascinato lungo la strada, dalla storie che avrei scoperto. L’attenzione alla biodiversità del territorio e le numerose iniziative di restituzione del paesaggio che questi lavori di scavo comportano sono impressionanti. Non parlo solo degli effetti prettamente legati alla costruzione del tunnel ma anche di quelli riguardanti l’isola vulcanica di Puketutu, dove viene trasportata la terra estratta dal cantiere sotterraneo. Prima che venisse sfruttata e irrimediabilmente trasformata per la costruzione dell’aeroporto di Auckland, Puketutu era un luogo sacro per i Māori. Grazie al nuovo cantiere si sta riportando l’isola alle sue sembianze originarie. In sostanza, i siti di scavo diffusi nella città, super organizzati, tecnologici e artificiali, sono in perfetta sintonia con la natura circostante, in un progetto di costruzione e ricostruzione, dal mio punto di vista più di ogni altra cosa, culturale. L’autenticità storica di un luogo è la chiave attraverso la quale prende forma la mia ricerca fotografica. Mi interessano i frammenti appartenenti a un passato lontano, dimenticato. Gli indizi parziali e tutto ciò che è nascosto o mancante sono spesso i protagonisti delle mie immagini.

AD: L’esperienza diretta del cantiere ha generato una serie di impressioni che hanno contribuito a formare il tuo approccio visivo. Nei nostri scambi hai più volte usato il Nautilus del capitano Nemo come riferimento atmosferico del trovarsi all’interno del tunnel e della TBM. Cercando su Internet, ho scoperto che Nautilus, oltre ad essere il nome del sommergibile che compare nei romanzi Ventimila leghe sotto i mari e L’isola misteriosa di J. Verne, è anche il nome del primo battello sommergibile costruito nel 1800 e del primo sottomarino a propulsione atomica costruito nel 1954. La parola nautilus viene dal nome di uno straordinario animale marino, un mollusco antichissimo che vive nella sua conchiglia a spirale ed è dotato di un sistema visivo primitivo: il suo occhio funziona come una camera oscura, in cui la messa a fuoco penalizza la luminosità e viceversa. Tutte suggestioni che ho poi ritrovato nelle tue immagini.

GP: Prima di arrivare, non avevo chiara la straordinaria dimensione del cantiere. Per raggiungere la TBM principale sono dovuta scendere con un ascensore in uno dei pozzi da cui veniva continuamente trasportata la terra appena estratta. In fondo, iniziava il tunnel. C’era un trenino ma ho deciso di muovermi a piedi per potermi fermare e fotografare. Ho camminato per circa due chilometri prima di vedere il fronte di scavo. All’inizio nel silenzio, poi tra rumori meccanici, voci e risate. Per chiunque non sia abituato a scenari di questo tipo, ritrovarsi nel cantiere di un tunnel sotto il mare evoca immaginari fantascientifici. Arrivati alla TBM, si ha davvero la sensazione di essere dentro un sottomarino. Ci sono diversi piani, una sala computer, impalcature, cavi e marchingegni di ogni sorta. Le numerose persone che ci lavorano, si muovono quasi in sincronia, a proprio agio, passandosi materiali, strumenti o un caffè. La parola nautilus racchiude bene l’atmosfera di questo lavoro. Fa riferimento non solo all’idea di avventura e scoperta ma anche al tunnel e al sottomarino, alle vedute dall’alto e alle foreste, ai misteri della Terra e alla paleontologia. In fondo, le nature morte con i fossili che ho fotografo all’Auckland War Memorial Museum sono i veri protagonisti di questa storia.

AD: Nel libro, le immagini delle conchiglie e dei fossili marini ritrovati nel cantiere si alternano a scorci del tunnel e del cantiere, a vedute di Auckland, della costa e della natura incontaminata e, in particolare, dell’isola di Puketutu.

GP: La sequenza che abbiamo scelto per il libro è un viaggio di andata e ritorno attraverso il paesaggio di Auckland e del cantiere, dal cielo al sottosuolo. La scelta di contrapporre gli elementi del cantiere agli scenari naturali circostanti è venuta notando la somiglianza tra la terra estratta dal tunnel e trasportata a Puketutu per la ricostruzione dei coni vulcanici originari e le rocce e le spiagge di sabbia lavica di quell’area. Le poche figure umane appaiono lontanissime e immerse in paesaggi sconfinati, mentre i fossili sono raccontati da molto vicino, osservati come creature preistoriche che nuotano nel mare. Come nei miei lavori passati, la materia è quindi al centro. Una materia che cambia consistenza, forma, posizione geografica, senso storico e significato culturale davanti ai nostri occhi.

AD: Il rapporto con la tua ricerca e pratica artistica, la materia, la memoria, l’invisibilità e la riscoperta, tutto sembra riportarci alla tua vicenda personale. Probabilmente una serie di coincidenze, alcune inaspettate, altre cercate, si sono allineate per indicarti la strada verso un nuovo lavoro.

GP: La mia fascinazione per la storia e per la riscoperta del passato, per ciò che è distante, sommerso o invisibile, ha sicuramente a che fare con il tempo passato ad ascoltare la mia bisnonna Giulia. Era una grande narratrice. Mi raccontava della sua infanzia e dei giochi che faceva con i suoi numerosi cugini, del padre assente e lontano, di quando i tedeschi le hanno bruciato la casa durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale e del lungo peregrinare attraverso l’Italia con i suoi figli. Tutto questo mi ha portata sin da bambina a pormi domande sul potere immaginifico della narrazione, sul modo in cui raccontiamo il passato e su come ci viene raccontato da altri. Io e Francesco non ci siamo mai conosciuti, eppure l’aver riportato ad Auckland la sua mappa della città, sulla quale aveva preso appunti per mostrare ai suoi genitori dove abitava e i posti che frequentava, mi ha emozionata. La sua storia affronta temi a me molto vicini, che ho intenzione di approfondire. Ho appena iniziato a sviluppare un nuovo progetto che parla dell’atto di scomparire e del paesaggio come testimonianza, e che è nato in seguito a riflessioni e appunti che ho preso durante il viaggio in Nuova Zelanda. Sono felice di ricominciare presto a fotografare.

1 Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide To Getting Lost, Canongate Books, Edinburgh 2017.

Rachele Maistrello and Alessandro Dandini de Sylva in Conversation

Who needs to travel thousands of miles to find the new? The most mysterious place on Earth is right beneath our feet.1

AD: In 1768, James Cook set sail on the Endeavour tasked with exploring the Pacific Ocean, observing the 1769 transit of Venus across the Sun and searching for evidence of the existence of the Terra Australis. The expedition crossed the Atlantic, rounded Cape Horn, arrived in Tahiti in time for the transit of Venus and continued on to New Zealand, before reaching the east coast of Australia in 1770. Cook was the first European to explore the coastline of the new continent and map it by drawing nautical charts and coastal views. A group of naturalists and artists led by Joseph Banks accompanied this valuable mapping with an equally precious collection and classification of numerous species of exotic plants and animals completely unknown to European science. A double mapping that I unexpectedly encountered in your work and discovered that deeply belongs to your view of the world.

RM: This approach has deep roots. Even in my childhood, the mapping of space followed double coordinates: classic space-time ones and other secret, labyrinthine ones that belonged to the world of my father, a keen ornithologist. For him, the seasons were marked by the late or early appearance of migratory species, geography was deduced not from the four cardinal points but from invisible trajectories of bird songs among the vegetation. Moving a few metres from home was enough to glean infinite possible worlds: a piece of bamboo was transformed into a three-note whistle, a branch of a common boxwood hedge into a very precise bow. Australia was his El Dorado: a reservoir of unique bird species, a place of unspoiled vegetation; it was the fuel of his most vivid dreams and the subject of the volumes that filled our bookcase. As time goes by, I’m noticing his coordinates in my own eye, like an inner puzzle, and discovering the great truth of his words: la vida es sueño.

AD: Your photographic campaign is probably the most mysterious of those realized so far. Entrusting you with the Brisbane site opened up storytelling possibilities and visual drifts that we hadn’t expected.

RM: When you contacted me to ask if I wanted to go to Australia, for me it was a synchronic event, an urge to probe a mythological narrative about my own origins. In a way, I felt like Estrella setting off for the South. But why, I wondered, did this synchronicity want me in Australia, yet not in my father’s beloved places of light, song and colour, but metres and metres below the surface, in the mud and darkness of an excavation for a gigantic infrastructure? Perhaps because, like Estrella, I was also hoping to find the origins of a family secret, which for her, it just so happens, was dowsing, or the art of finding water in the underground depths?

AD: Estrella’s South has to do with an inner geography whose coordinates are memory and dreams. A territory that you’ve decided to explore by following anti-narrative paths and tracing maps that, like the “songlines” described by Bruce Chatwin, superimpose identity, culture and landscape.

RM: I knew that the work I would bring home would follow an inner logic, my own personal songline, and that I would have to have faith in what might at first seem even outlandish or illogical. My inner guide while exploring the site and the city was in fact Bruce Chatwin, the man who, upon his return from Australia, would recount the famous songlines, or maps of the land that the Aborigines handed down orally, constructing a territorial and ancestral geography of their ancestors. What songline would reveal itself to me in the Ghella excavations, up and down between the sunny world and the damp darkness of the caves?

AD: Looking at your work, you get the feeling that you’ve done the opposite of the other artists involved in the project. Instead of projecting the landscape of the construction site onto your imagination, you poured your imagination into the construction site, populating the excavations with magical creatures, mysterious figures and nocturnal animals.

RM: The first site I visited was Albert Site. It’s the one that I felt, more than any other excavation, was immediately the focus of everything. A few weeks before my arrival, a huge coiled carpet python (Morelia spilota) had been found right at the entrance to the construction site and had been released into the wild, as required by Australian law, in the nearest park, the City Botanic Gardens, a short walk from my hotel. Here were the first coordinates of the map I was looking for. My eye thus immediately turned to Albert Site by day and the botanical garden by night, transforming everyday life into an eclipse of darkness and humidity. At dusk, from the construction site, a strangely protective hypnotic and magnetic place, I would run to the botanical garden to see the nocturnal animals appearance. First the giant bats that seemed to come from the realm of the excavation, then, in the dark, the possums, shy animals that once led me to the centre of the park towards an unexpected meeting: a girl, an alter ego of mine from ten or fifteen years ago. She was alone facing her fears, risking a little, just like me.

AD: Alongside your observation of the construction site, you also gathered information that allowed you to complete an important ethnographic survey involving workers, engineers and technicians in the space of a few days. How did you manage to intercept their suggestions and to what extent did the imagery that emerged change or amplify your view?